Portraiture at the edge

The portraiture of Amy Adams and Louise te Poele could not be any more different. Both were contestants at this year’s Hyeres Fashion and Photography Festival, presenting their work to the jury - and the visitors.

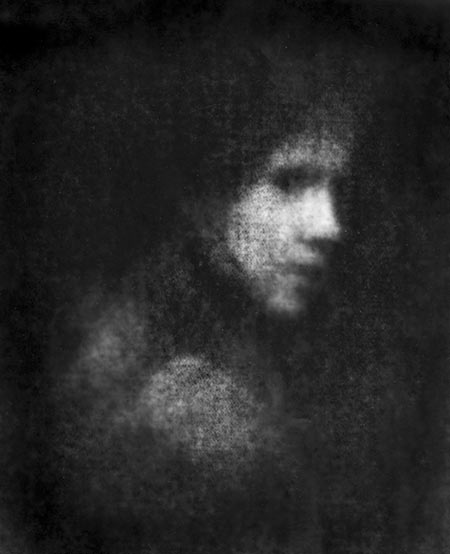

Amy offered a series of stark, b/w images, which asked the viewer to spend time with them to discover the faces and their expressions. Starting from movies taken with a video camera from her (former) apartment, with the view facing the platform of a train station, Amy isolated just the faces of her subjects, enlarged them and then produced an actual photographic negative for silver-gelatin prints, thus marrying modern technology with “old-school” photography. Given the lack of resolution of the video camera, electronic noise is clearly visible in a somewhat unexpected form, since the grain usually found in b/w processing is of an entirely different nature.

In a nutshell, Amy’s work combines the stealth portraiture work done by Philip-Lorca diCorcia with the explorations of digital artifacts for which Thomas Ruff is well known (and you can throw your favourite b/w printer into the mix for the final result). As a technique, this approach shows how contemporary practitioners of photography are not afraid to deviate from photographic orthodoxy: The image is what matters. Whatever it takes to get there is simply made to work.

In contrast, Louise’s portraiture is deceptively simple, in that it presents, well, portraits. But when one starts to look at details one realizes that things are not that simple. Some digital processing did clearly happen. What is more, some of the pairings of portraits in fact show just a single person, seen from two different angles. But to get there one has to get past the fact that many of the portraits looks so extremely unflattering.

Of course, we are aware of the fact that portraiture does not necessarily have to be flattering (with our own portraits we are usually less generous: They better look just the way we want them to look!). But can we allow portraiture to be this unflattering?

Of course, in some cases we relish an unflattering portrait (think Arnold Newman’s famous portrait of convicted war criminal and German industrialist Alfried Krupp). But usually, we don’t, because it strikes us as almost cruel. When I asked her whether she had ever shown the portraits to the subjects (people living in a small, somewhat isolated village in Holland) Louise told me that she had. In fact, her subjects loved the photos! “That’s exactly me,” one of them told her.

So where does that leave us with our thinking about unflattering portraiture?

What is striking is how Amy’s and Louise’s portraiture have one thing in common: They challenge our views of what a portrait is, what it can do, and what it should or maybe should not do. Pieter Hugo famously produced a body of work called “Looking Aside” - images of albinos, blind and very old people whose faces one is not supposed to “stare” at. With just a portrait (and the persons not present), there is nothing left for us but to look. In similar ways, both Amy and Louise produced portraiture that we could consider to be problematic: We don’t think it is appropriate any longer to take photos of people without their knowledge, and we don’t think portraiture should be this revealing.

But these kinds of restrictions are conventions. Make no mistake, the idea behind these bodies of work is not to do away with social restrictions. Most art is not aiming for a free-for-all (some is, but it usually gets old very quickly, especially in cases where one realizes that what postures as iconoclasm is just that: a posture, the art-world equivalent of radio “shock jocks” [think Dash Snow]). But some art is willing to push the boundaries (even of good taste) to see where it leads us. Amy’s and Louise’s portraiture might be taken as such art - they certainly challenge us to look at people in a way we are not used to.