Review: Hashem Ek Madani: Studio Practices

Photographic portrait studios have been well established as treasure troves of photography. The sheer number of yet-to-be discovered photographers who have been (or were) taking people’s photos in their portrait studios is hard to estimate. For me, the value of most of those discoveries is two-fold: First, it is amazing how many unknown photographers are (or were) in fact true masters of portraiture, often deviating quite a bit from standard practice. Second, with a larger collection of photography, the studios’ archives become a mirror of the society they are (or were) embedded in.

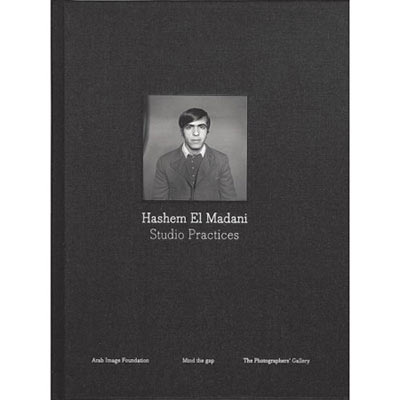

Hashem El Madani: Studio Practices is another fine example of this genre (assuming we’d want to call it a genre). Born in 1928, Hashem El Madani has been taking portraits in the Lebanese town of Saida for many decades, amassing an archive that contains - if the book is to be believed - over 500,000 images. I have no way of confirming this number. It sounds like a lot - with 60 years of practice (Madani started to take photos in 1948) that would be 8,333 photos per year or 22 photos a day. Entirely possible. Gene Smith took 17,000 photos in Pittsburgh in that year or two he was there, Robert Frank had “over 20,000” for “The Americans”, and for his recent hipster extravaganza “I Know Where the Summer Goes” Ryan McGinley supposedly took “150,000 photographs” (these numbers were all found online).

Out of this huge archive, Hashem El Madani: Studio Practices presents an impressive and beautiful collection, sorted in a somewhat typological way (as an aside, it escapes me why the editor(s) decided to include some images sideways in some of those sets). You got it all: weddings, bodybuilders, tough and not-so-tough guys posing with Kalashnikovs, some tough guys posing without their guns (explains the photographer: “These are Syrians. […] They used to come unarmed to the studio.”), babies, standard (passport style) portraits, retouched portraits (“These two are members of the Syrian Intelligence. They had their guns against their waists. They asked me for a hand-coloured portrait which they never picked up.”), people posing with a radio (“In the 1940s and 1950s people loved to pose with a radio.”), etc etc etc. And all that comes with an interview with the photographer, an introduction, in a book of a size that doesn’t require a big table (or lap) to place it on - truly wonderful!