Thoughts on Portraiture

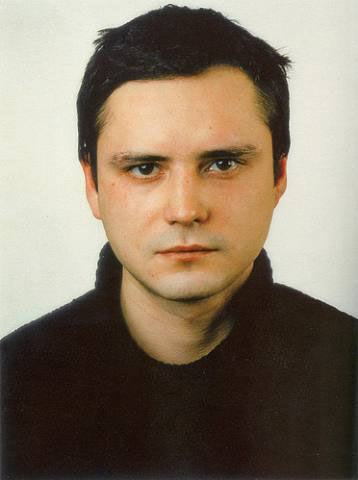

People often tell me that Thomas Ruff’s portraits are boring. What does that mean: “boring”? How can a portrait be boring?

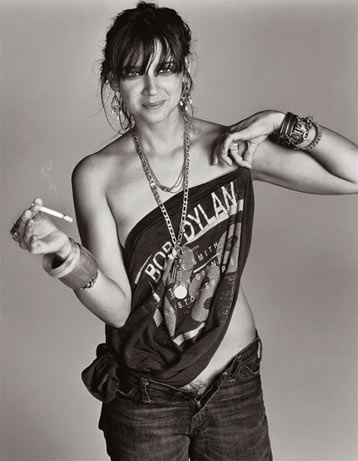

Maybe it’s because what we really want to see is something like this:

This portrait of Chan Marshall (aka “Cat Power”) by Richard Avedon appears to be not boring. We feel entertained. Is that what it is? We might even feel like we learned something. While Thomas Ruff doesn’t show us anything about S. Ergolovitch, Richard Avedon treats us (if we want to call it that) to seeing something about Chan Marshall, and boy, it’s not a pretty sight.

But then, is that the portrait of Chan Marshall that we want to have? “I was so drunk I could barely stand up,” the subject remembers the session: “My organs were so messed up from drinking I was in physical pain. I couldn’t zip up my pants because my stomach was killing me. I didn’t even realize I wasn’t wearing underwear until the magazine came out. […] I had to explain to my grandmother that this was the definitive photographer of the 20th century.”

In other words, if it hadn’t been for the “definitive photographer of the 20th century” (let’s ignore this assessment) things would have been even more unpleasant for Chan Marshall than they already were.

Of course, in a culture centered on entertainment we usually don’t care all that much about what the people might feel whose images we stare at day in, day out. But maybe we do want to care a little bit about what we think these images say, and we might want to think about whether the person behind the portrait might in fact be somebody completely different.

Because, in the end, portraiture involves three parties, namely the photographer, the subject, and the viewer; and what a portrait says is determined by the immensely tricky interaction between all these parties (and not just between the photographer and the subject).

Which brings us back to Thomas Ruff’s portrait. What do we learn about S. Ergolovitch? Do we really learn that much less about him than about Chan Marshall in Avedon’s portrait? Sure, S. Ergolovitch does not look drunk (his pants might be unbuttoned, but we can’t see that), but S. Ergolovitch might have been drunk at some stage, just with no camera present.

Maybe we find Thomas Ruff’s portrait of S. Ergolovitch boring, because photographer and subject refuse to give us something to cling on to? When we feel bored does that not in fact say something about us and our way to approach photographic portraits? But is that really boring?

(to be continued…)