The case for mining photography archives

Let’s face it: Photographers are a pretty conservative bunch of people. While we all know that photographer X might have taken thousands of images, what do we get to see? The same old well-known ones. While we all know that the archive of agency/foundation/… Y contains thousands and thousands of images, what do we get to see? The same old well-known stuff. It gets even more depressing when you look at photobooks. Some publishers have been working with photographers, reissuing older work, but what do we get? Well, we either get an exact reissue, or we get one of those compilations of ten volumes in a limited-edition box for only $500 that I made fun of on April 1st (there are a few exception, of course). This is a huge lost opportunity, both for the artists/archives and for people who love looking at photography. (more)

The cases of photography archives are probably more obvious than those of photobooks. The way I think about a photography archive is somewhat informed by some of the things I was working on in the past. The first is what’s usually called data mining. Of course, you cannot literally apply data mining to photography archives, but you can apply the general principle, namely sifting through the archive to extract new information or to edit new sets of images that present something you have not seen before.

This is what I tried to do when LIFE contacted me about being a guest editor (I mentioned this earlier). What I did was to literally look at thousands of images - only picking date ranges to narrow the selections down, to see where that would take me. The idea for the edit came after spending quite a bit of time with all those images. So you could imagine that new pairs of eyes would sift through the archives of agencies or foundations, to extract new, unseen edits.

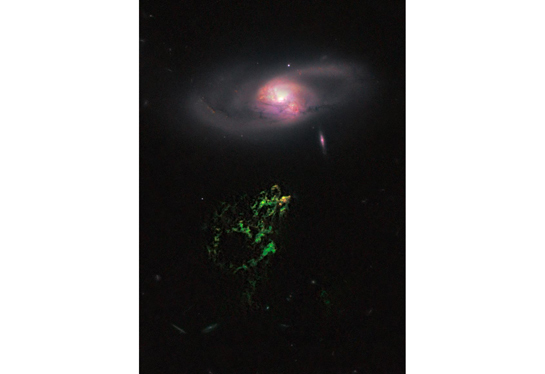

The benefits of having new pairs of eyes look was brought home a little while ago, when Hanny van Arkel, a Dutch schoolteacher, found the green blog in the image above. Astronomers have been pretty savvy in this regard:There are so many photographs of the sky now that it’s simply not possible for them to look at everything. So there’s Galaxy Zoo: Anyone can sign up and look around. Like Hanny van Arkel, they might find something.

Without eyes looking at it, any archive, as nice as it might be, is basically dead. What’s the point of an archive if nobody looks at it?

The case of photography archives is somewhat related to the case of Flickr. Flickr might be the most obvious case of a living photography archive. Facebook might have more photographs, but since Facebook changes their rules every other day, the site is unusable as an archive for anyone other than the company itself (which is, let’s face it, the idea). In the case of Flickr, you have, for example, La Pura Vida, which, in a sense, data mines the site to extract photography.

Having new eyes look at older archives of photographs of course could also lead to fantastic insights into a photographer’s work. This is not to say that the old edits are bad. But who knows what kinds of new edits someone smart, with a great eye, might come up with? Of course, the old edit is always informed by its times and circumstances - but maybe an old, classic edit could get radically transformed into something that suddenly looks fresh again?

The same is true for photobooks. Photobooks tend to be collaborations, where an editor works with a photographer and a designer. So why do most photobook edits remain static? Most people change as they get older, so you would imagine that a photographer might see her or his work with his “older” eyes and change the edit, to reflect a new view. Or a different editor might bring a different perspective to the work. It wouldn’t really be the same book any longer, but that’s not the point.

Would a different perspective be so bad? Different here doesn’t mean better or worse. It really means just different.

This is not to say that old books or bodies of work need a new edit per se. Hey, if you think they’re perfect by all means keep things as they are. A lot of photobooks are so good that they look fresh every time you open them again.

But still, I think there are interesting, largely unexplored opportunities here… and some agency, foundation, publisher and/or photographer might just pick them up.